Rewriting

In mathematics, computer science, and logic, rewriting covers a wide range of (potentially non-deterministic) methods of replacing subterms of a formula with other terms. What is considered are rewriting systems (also known as rewrite systems or reduction systems). In their most basic form, they consist of a set of objects, plus relations on how to transform those objects.

Rewriting can be non-deterministic. One rule to rewrite a term could be applied in many different ways to that term, or more than one rule could be applicable. Rewriting systems then do not provide an algorithm for changing one term to another, but a set of possible rule applications. When combined with an appropriate algorithm, however, rewrite systems can be viewed as computer programs, and several declarative programming languages are based on term rewriting.

Contents |

Intuitive examples

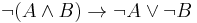

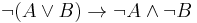

Logic

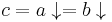

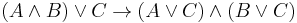

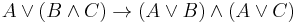

In logic, the procedure for determining the conjunctive normal form (CNF) of a formula can be conveniently written as a rewriting system. The rules of such a system would be:

where the symbol ( ) indicates that an expression matching the left side of the rule can be rewritten to one formed by the right side. In this system, we can perform a rewrite from left to right only when the logical interpretation of the left side entails that of the right).

) indicates that an expression matching the left side of the rule can be rewritten to one formed by the right side. In this system, we can perform a rewrite from left to right only when the logical interpretation of the left side entails that of the right).

Abstract rewriting systems

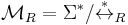

From the above examples, it's clear that we can think of rewriting systems in an abstract manner. We need to specify a set of objects and the rules that can be applied to transform them. The most general (unidimensional) setting of this notion is called an abstract reduction system, (abbreviated ARS), although more recently authors use abstract rewriting system as well.[1] (The preference for the word "reduction" here instead of "rewriting" constitutes a departure from the uniform use of "rewriting" in the names of systems that are particularizations of ARS. Because the word "reduction" does not appear in the names of more specialized systems, in older texts reduction system is a synonym for ARS).[2]

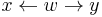

An ARS is simply a set A, whose elements are usually called objects, together with a binary relation on A, traditionally denoted by →, and called the reduction relation, rewrite relation[3] or just reduction.[2] This (entrenched) terminology using "reduction" is a little misleading, because the relation is not necessarily reducing some measure of the objects; this will become more apparent when we discuss string rewriting systems further in this article.

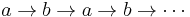

Example 1. Suppose the set of objects is T = {a, b, c} and the binary relation is given by the rules a → b, b → a, a → c, and b → c. Observe that these rules can be applied to both a and b in any fashion to get the term c. Such a property is clearly an important one. Note also, that c is, in a sense, a "simplest" term in the system, since nothing can be applied to c to transform it any further. This example leads us to define some important notions in the general setting of an ARS. First we need some basic notions and notations.[4]

is the transitive closure of

is the transitive closure of  , where = is the identity relation, i.e.

, where = is the identity relation, i.e.  is the smallest preorder (reflexive and transitive relation) containing

is the smallest preorder (reflexive and transitive relation) containing  . It is also called the reflexive transitive closure of

. It is also called the reflexive transitive closure of  .

. is

is  , that is the union of the relation → with its inverse relation, also known as the symmetric closure of

, that is the union of the relation → with its inverse relation, also known as the symmetric closure of  .

. is the transitive closure of

is the transitive closure of  , that is

, that is  is the smallest equivalence relation containing

is the smallest equivalence relation containing  . It is also known as the reflexive transitive symmetric closure of

. It is also known as the reflexive transitive symmetric closure of  .

.

Normal forms, joinability and the word problem

An object x in A is called reducible if there exist some other y in A and  ; otherwise it is called irreducible or a normal form. An object y is called a normal form of x if

; otherwise it is called irreducible or a normal form. An object y is called a normal form of x if  , and y is irreducible. If x has a unique normal form, then this is usually denoted with

, and y is irreducible. If x has a unique normal form, then this is usually denoted with  . In example 1 above, c is a normal form, and

. In example 1 above, c is a normal form, and  . If every object has at least one normal form, the ARS is called normalizing.

. If every object has at least one normal form, the ARS is called normalizing.

A related, but weaker notion than the existence of normal forms is that of two objects being joinable: x and y are said joinable if there exists some z with the property that  . From this definition, it's apparent one may define the joinability relation as

. From this definition, it's apparent one may define the joinability relation as  , where

, where  is the composition of relations. Joinability is usually denoted, somewhat confusingly, also with

is the composition of relations. Joinability is usually denoted, somewhat confusingly, also with  , but in this notation the down arrow is a binary relation, i.e. we write

, but in this notation the down arrow is a binary relation, i.e. we write  if x and y are joinable.

if x and y are joinable.

One of the important problems that may be formulated in an ARS is the word problem: given x and y are they equivalent under  ? This is a very general setting for formulating the word problem for the presentation of an algebraic structure. For instance, the word problem for groups is a particular case of an ARS word problem. Central to an "easy" solution for the word problem is the existence of unique normal forms: in this case if two objects have the same normal form, then they are equivalent under

? This is a very general setting for formulating the word problem for the presentation of an algebraic structure. For instance, the word problem for groups is a particular case of an ARS word problem. Central to an "easy" solution for the word problem is the existence of unique normal forms: in this case if two objects have the same normal form, then they are equivalent under  . The word problem for an ARS is undecidable in general.

. The word problem for an ARS is undecidable in general.

The Church-Rosser property and confluence

An ARS is said to possess the Church-Rosser property if and only if  implies

implies  . In words, the Church-Rosser property means that the reflexive transitive symmetric closure is contained in the joinability relation. Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser proved in 1936 that lambda calculus has this property;[5] hence the name of the property.[6] (The fact that lambda calculus has this property is also known as the Church-Rosser theorem.) In an ARS with the Church-Rosser property the word problem may be reduced to the search for a common successor. In a Church-Rosser system, an object has at most one normal form; that is the normal form of an object is unique if it exists, but it may well not exist.

. In words, the Church-Rosser property means that the reflexive transitive symmetric closure is contained in the joinability relation. Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser proved in 1936 that lambda calculus has this property;[5] hence the name of the property.[6] (The fact that lambda calculus has this property is also known as the Church-Rosser theorem.) In an ARS with the Church-Rosser property the word problem may be reduced to the search for a common successor. In a Church-Rosser system, an object has at most one normal form; that is the normal form of an object is unique if it exists, but it may well not exist.

Several different properties are equivalent to the Church-Rosser property, but may be simpler to check in any particular setting. In particular, confluence is equivalent to Church-Rosser. The notion of confluence can be defined for individual elements, something that's not possible for Church-Rosser. An ARS  is said:

is said:

- confluent if and only if for all w, x, and y in A,

implies

implies  . Roughly speaking, confluence says that no matter how two paths diverge from a common ancestor (w), the paths are joining at some common successor. This notion may be refined as property of a particular object w, and the system called confluent if all its elements are confluent.

. Roughly speaking, confluence says that no matter how two paths diverge from a common ancestor (w), the paths are joining at some common successor. This notion may be refined as property of a particular object w, and the system called confluent if all its elements are confluent. - locally confluent if and only if for all w, x, and y in A,

implies

implies  . This property is sometimes called weak confluence.

. This property is sometimes called weak confluence.

Theorem. For an ARS the following conditions are equivalent: (i) it has the Church-Rosser property, (ii) it is confluent.[7]

Corollary.[8] In a confluent ARS if  then

then

- If both x and y are normal forms, then x = y.

- If y is a normal form, then

Because of these equivalences, a fair bit of variation in definitions is encountered in the literature. For instance, in Bezem et al. 2003 the Church-Rosser property and confluence are defined to be synonymous and identical to the definition of confluence presented here; Church-Rosser as defined here remains unnamed, but is given as an equivalent property; this departure from other texts is deliberate.[9] Because of the above corollary, one may define a normal form y of x as an irreducible y with the property that  . This definition, found in Book and Otto, is equivalent to common one given here in a confluent system, but it is more inclusive in a non-confluent ARS.

. This definition, found in Book and Otto, is equivalent to common one given here in a confluent system, but it is more inclusive in a non-confluent ARS.

Local confluence on the other hand is not equivalent with the other notions of confluence given in this section, but it is strictly weaker than confluence.

Termination and convergence

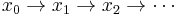

An abstract rewriting system is said to be terminating or noetherian if there is no infinite chain  . In a terminating ARS, every object has at least one normal form, thus it is normalizing. The converse is not true. In example 1 for instance, there is an infinite rewriting chain, namely

. In a terminating ARS, every object has at least one normal form, thus it is normalizing. The converse is not true. In example 1 for instance, there is an infinite rewriting chain, namely  , even though the system is normalizing. A confluent and terminating ARS is called convergent. In a convergent ARS, every object has a unique normal form. But it is sufficient for the system to be confluent and normalizing for a unique normal to exist for every element, as seen in example 1.

, even though the system is normalizing. A confluent and terminating ARS is called convergent. In a convergent ARS, every object has a unique normal form. But it is sufficient for the system to be confluent and normalizing for a unique normal to exist for every element, as seen in example 1.

Theorem (Newman's Lemma): A terminating ARS is confluent if and only if it is locally confluent.

String rewriting systems

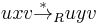

A string rewriting system (SRS), also known as semi-Thue system, exploits the free monoid structure of the strings (words) over an alphabet to extend a rewriting relation, R to all strings in the alphabet that contain left- and respectively right-hand sides of some rules as substrings. Formally a semi-Thue systems is a tuple  where

where  is a (usually finite) alphabet, and R is a binary relation between some (fixed) strings in the alphabet, called rewrite rules. The one-step rewriting relation relation

is a (usually finite) alphabet, and R is a binary relation between some (fixed) strings in the alphabet, called rewrite rules. The one-step rewriting relation relation  induced by R on

induced by R on  is defined as: for any strings s, and t in

is defined as: for any strings s, and t in

if and only if there exist x, y, u, v in

if and only if there exist x, y, u, v in  such that s = xuy, t = xvy, and u R v. Since

such that s = xuy, t = xvy, and u R v. Since  is a relation on

is a relation on  , the pair

, the pair  fits the definition of an abstract rewriting system. Obviously R is subset of

fits the definition of an abstract rewriting system. Obviously R is subset of  . If the relation

. If the relation  is symmetric, then the system is called a Thue system.

is symmetric, then the system is called a Thue system.

In a SRS, the reduction relation  is compatible with the monoid operation, meaning that

is compatible with the monoid operation, meaning that  implies

implies  for all strings x, y, u, v in

for all strings x, y, u, v in  . Similarly, the reflexive transitive symmetric closure of

. Similarly, the reflexive transitive symmetric closure of  , denoted

, denoted  , is a congruence, meaning it is an equivalence relation (by definition) and it is also compatible with string concatenation. The relation

, is a congruence, meaning it is an equivalence relation (by definition) and it is also compatible with string concatenation. The relation  is called the Thue congruence generated by R. In a Thue system, i.e. if R is symmetric, the rewrite relation

is called the Thue congruence generated by R. In a Thue system, i.e. if R is symmetric, the rewrite relation  coincides with the Thue congruence

coincides with the Thue congruence  .

.

The notion of a semi-Thue system essentially coincides with the presentation of a monoid. Since  is a congruence, we can define the factor monoid

is a congruence, we can define the factor monoid  of the free monoid

of the free monoid  by the Thue congruence in the usual manner. If a monoid

by the Thue congruence in the usual manner. If a monoid  is isomorphic with

is isomorphic with  , then the semi-Thue system

, then the semi-Thue system  is called a monoid presentation of

is called a monoid presentation of  .

.

We immediately get some very useful connections with other areas of algebra. For example, the alphabet {a, b} with the rules { ab → ε, ba → ε }, where ε is the empty string, is a presentation of the free group on one generator. If instead the rules are just { ab → ε }, then we obtain a presentation of the bicyclic monoid. Thus semi-Thue systems constitute a natural framework for solving the word problem for monoids and groups. In fact, every monoid has a presentation of the form  , i.e. it may be always be presented by a semi-Thue system, possibly over an infinite alphabet.

, i.e. it may be always be presented by a semi-Thue system, possibly over an infinite alphabet.

The word problem for a semi-Thue system is undecidable in general; this result is sometimes known as the Post-Markov theorem.[10]

Term rewriting systems

A term rewriting system (TRS) is a rewriting system where the objects are terms, or expressions with nested sub-expressions. For example, the system shown under Logic above is a term rewriting system. The terms in this system are composed of binary operators  and

and  and the unary operator

and the unary operator  . Also present in the rules are variables, which are part of the rules themselves rather than the term; these each represent any possible term (though a single variable always represents the same term throughout a single rule).

. Also present in the rules are variables, which are part of the rules themselves rather than the term; these each represent any possible term (though a single variable always represents the same term throughout a single rule).

The term structure in such a system is usually presented using a grammar. In contrast to string rewriting systems, whose objects are flat sequences of symbols, the objects of a term rewriting system form a term algebra, which can be visualized as a tree of symbols, the structure of the tree fixed by the signature used to define the terms.

The system given under Logic above is an example of a term rewriting system.

Graph rewriting systems

A generalization of term rewrite systems are graph rewrite systems, operating on graphs instead of (ground-) terms / their corresponding tree representation.

Trace rewriting systems

Trace theory provides a means for discussing multiprocessing in more formal terms, such as via the trace monoid and the history monoid. Rewriting can be performed in trace systems as well.

Philosophy

Rewriting systems can be seen as programs that infer end-effects from a list of cause-effect relationships. In this way, rewriting systems can be considered to be automated causality provers.

Properties of rewriting systems

Observe that in both of the above rewriting systems, it is possible to get terms rewritten to a "simplest" term, where this term cannot be modified any further from the rules in the rewriting system. Terms which cannot be written any further are called normal forms. The potential existence or uniqueness of normal forms can be used to classify and describe certain rewriting systems. There are rewriting systems which do not have normal forms: a trivial example is the rewriting system on two terms a and b with a → b, b → a.

The property exhibited above where terms can be rewritten regardless of the choice of rewriting rule to obtain the same normal form is known as confluence. The property of confluence is linked with the property of having unique normal forms.

See also

- Critical pair (logic)

- Knuth-Bendix completion algorithm

- L-systems specify re-writing that is done in parallel.

- Regulated rewriting

- Rho calculus

Notes

- ^ Bezem et al, p. 7,

- ^ a b Book and Otto, p. 10

- ^ Bezem et al, p. 7

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, pp. 8-9

- ^ Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser. Some properties of conversion. Trans. AMS, 39:472-482, 1936

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, p. 9

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, p. 11

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, p. 12

- ^ Bezem et al, p.11

- ^ Martin Davis et al. 1994, p. 178

Further reading

- Baader, Franz; Nipkow, Tobias (1999). Term rewriting and all that. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77920-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=N7BvXVUCQk8C&dq. 316 pages. A textbook suitable for undergraduates.

- Marc Bezem, Jan Willem Klop, Roel de Vrijer ("Terese"), Term Rewriting Systems, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0521391156. This is the most recent comprehensive monograph. It uses however a fair deal of non-yet-standard notations and definitions. For instance the Church-Rosser property is defined to be identical with confluence.

- Ronald V. Book and Friedrich Otto, String-Rewriting Systems, Springer (1993).

- Nachum Dershowitz and Jean-Pierre Jouannaud Rewrite Systems, Chapter 6 in Jan van Leeuwen (Ed.), Handbook of Theoretical Computer Science, Volume B: Formal Models and Sematics., Elsevier and MIT Press, 1990, ISBN 0-444-88074-7, pp. 243–320. The preprint of this chapter is freely available from the authors, but it misses the figures.

External links

- The Rewriting Home Page

- IFIP Working Group 1.6

- Researchers in rewriting by Aart Middeldorp, University of Innsbruck

- Termination Portal

(

( (

(

(

( ,

,